Richard’s Tale – Locked Up: When Healing Can’t Break the Cycle

Richard’s Tale is the piece that changes everything about how we understand The Tales. We’ve seen Vincent – born into addiction, locked up before he ever committed a crime. We’ve seen Screech and Jenny – orphaned twins, one who murdered the other without ever knowing they were siblings. But Richard? Richard is us. The person watching this unfold, trying to make sense of it, trying to do the right thing in a system designed to produce tragedy.

This is what happens when you achieve class consciousness while working for the class enemy. This is what happens when therapy heals your trauma but can’t fix the structure that caused it. This is moral injury rendered in five movements, from boom bap to uplifting piano to the crushing reality of going back to work.

Richard’s first day back after shooting a 14-year-old boy: he arrests Vincent. Both men locked up. One in a cell, one in a role. Both trapped by the same machinery.

Richard’s Tale begins at 4:55 – after Vincent’s Bedroom performance ends

The Story So Far: Understanding the Cycle of Samsara

Before we dive into Richard’s Tale, you need to understand what Richard is processing. The Tales aren’t separate stories – they’re an intergenerational web of trauma, and Richard is caught in the middle of it.

Violet’s Tale (2005): Violet, abused by her father then by her boyfriend Stevie, is beaten while nine months pregnant. She dies in hospital, but her twins survive: Jenny and Screech.

Jenny’s Tale (2015): Jenny, now grown, walking home alone in London, is attacked and murdered by a 14-year-old boy named Screech (also known as James). He doesn’t know she’s his twin sister. She doesn’t know he’s her twin brother. They were separated at birth when their mother died.

Screech’s Tale (2019): After killing Jenny, Screech runs to his mate Patrick’s flat, but Patrick’s not home. Panicking, Screech calls his girlfriend who rejects him. When police arrive, Screech – high on adrenaline and weed – charges at Officer Richard with a blade. Richard shoots him four times in the chest. Screech dies on the street, one road away from his twin sister Jenny’s body.

Vincent’s Tale: Vincent, born to an addicted mother, locked up by poverty and trauma before he ever saw a cell, gets into a fight with someone in an alleyway. Hears the cops coming, smashes a bottle, stabs the person he’s fighting. Richard arrests him.

That’s where Richard’s Tale begins: in the police van, driving Vincent to custody, processing what he’s done and what he’s seen.

The Cycle of Samsara

Samsara is a Buddhist and Hindu concept referring to the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth – the wheel of suffering that perpetually turns.

In Buddhist philosophy, beings are trapped in samsara until they achieve enlightenment and break free from the patterns of suffering and desire that bind them.

In Richard’s Tale, Ren uses “the cycle of samsara, always was, quite amusing” with bitter irony. The cycle here is intergenerational trauma and systemic violence:

- Violet (abused) → dies giving birth → twins orphaned and separated

- Screech and Jenny → shaped by trauma they never understood → Screech kills Jenny unknowingly

- Richard → traumatised by shooting Screech → processes grief → returns to arrest Vincent

- Vincent → born into the cycle → continues it

No one escapes. The wheel keeps turning. Richard’s “acceptance” doesn’t break the cycle – it just allows him to keep functioning within it. That’s the cruel joke: individual healing can’t fix systemic suffering.

Part 1: “Locked Up” – The Cop Car Confession

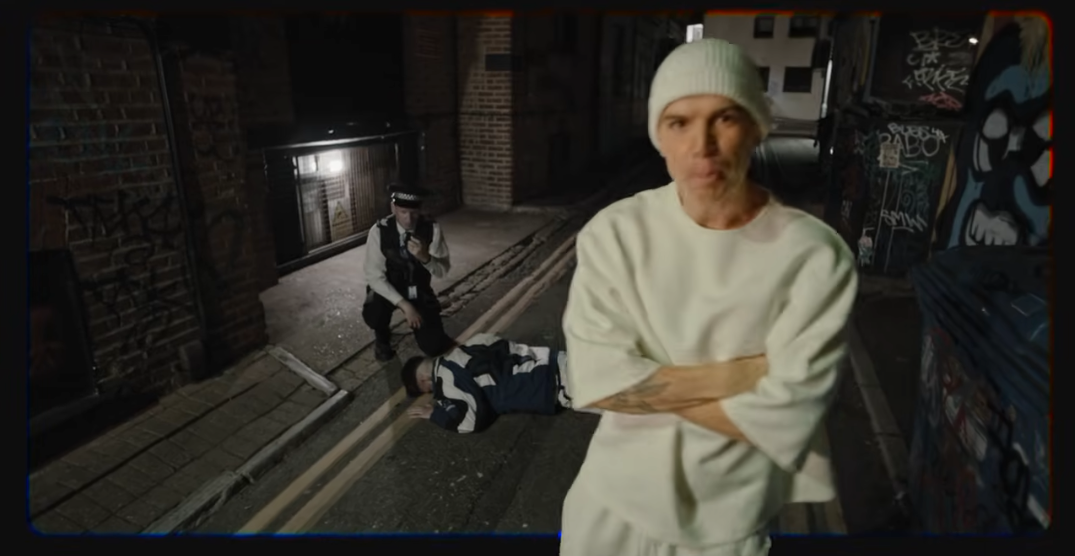

Richard driving Vincent to custody – both men locked up in different ways

The track opens with 90s boom bap hip-hop – hard, driving, systematic. Richard’s in the driver’s seat of a police van. Vincent’s in the back. And Ren, as narrator, is giving us Richard’s perspective on what he’s seeing.

Stand on my Miranda, my right to remain violent

One man’s resistance is another man’s tyrant

When tyrants make the law, they go to war with non-compliance”

That opening line – “my right to remain violent” – is a subversion of Miranda rights (“you have the right to remain silent”). Richard has the state’s monopoly on violence. His violence is legal. Sanctioned. Required.

“One man’s resistance is another man’s tyrant” – this is Richard understanding that from Vincent’s perspective, the police aren’t protectors, they’re oppressors. The laws weren’t made to help people like Vincent – they were made to control them.

Kiddie grew up fast, pulled his socks up, chop, chop

Keep that credit topped up

Time is money, tick, tock,

Quantify the price upon your soul and then it’s chop shop”

Richard sees it. Vincent was never free. “Locked up since his mother knocked up” – born into conditions that guaranteed this outcome. The “chop shop” isn’t just crime, it’s the system that commodifies souls, that turns human beings into economic units, that chops them up and sells the parts.

From my clinical perspective: This is Richard demonstrating what we call “social determinants of health” awareness. He’s not just seeing Vincent as a criminal who made bad choices. He’s seeing Vincent as the predictable outcome of poverty, neglect, trauma, and a system designed to extract rather than support.

When Richard arrested Vincent in Self Portrait, he saw “a boy with a guitar, bruised and battered on his knees.” Not a threat. Not a villain. A casualty.

Vinny spent his life a vessel

For the musings of the devil

Repetition caused some issues

Turn the Hyde into a Jekyll

Building pressure in the kettle

Bubble up to boiling level”

“Not particularly special” – Vincent’s not an exception. He’s the rule. This is what the system produces. The “musings of the devil” could be addiction, mental illness, rage – but really, it’s poverty and powerlessness made manifest. The “repetition” (that déjà vu religion from The Bedroom) turns Jekyll into Hyde. The pressure builds until the kettle explodes.

And Richard knows this because he’s seen it. He’s processed Screech – another kid the system failed, another explosion waiting to happen.

The one that serves you alcohol then sells you your sobriety

The one that sells you sex as it pedestals virginity

The one where we elect these lying pests with gullibility”

This is Richard’s political awakening. He’s not just seeing individual failures – he’s seeing systemic contradictions. A society that creates the conditions for addiction, then criminalises it. That sexualises everything, then shames desire. That lies to us, then blames us for believing.

“Never mind, just a victim of society” – said with bitter irony. Because society doesn’t accept that excuse. You’re supposed to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, even when you were never given boots.

Fed tarantulas, come live

Nine to the nine, to the nine for his crimes

Timelines intersect, Richard’s fate was designed”

“Richard’s fate was designed” – this is the key line. Richard’s not just a cop doing his job. He’s trapped too. His timeline intersected with Screech’s, with Vincent’s, with this entire cycle. He’s part of the machinery he’s beginning to understand.

Both men in this police van are locked up. Vincent’s going to a cell. Richard’s locked in a role he can’t escape.

Part 2: “Set The Scene” – The Trauma That Started It All

2019: Richard processes the aftermath of shooting Screech

The beat changes. We’re no longer in the police van – we’re flashing back to 2019, the night Richard shot Screech. Ren (as narrator) is standing there with Richard, who’s looking down at a 14-year-old boy’s body.

The music shifts to double-time rap, frantic and chaotic, then sonically slows down at “slo-mo” before continuing. It’s disorienting – which is exactly what trauma does to time perception.

Richard, and a boy named Screech

The hands of fate, they touch and reach

Siblings buried, blood, it bleeds, etched in Richard’s memories”

“Siblings buried, blood, it bleeds” – Richard knows. He knows that Screech just killed his own twin sister. He knows that neither of them knew they were related. He knows that Violet died giving birth to them. He knows the whole tragic cycle.

And it’s “etched in Richard’s memories” – this isn’t something he can forget. This is the image that will haunt him: a 14-year-old boy he shot, who’d just killed his own twin.

Hitting the bottle to soften the blow, when the war’s with yourself then there’s nowhere to go

And his friends on the force, they don’t call, they don’t show

Go to therapy regularly, seem to plateau”

The clinical reality of police trauma: This is textbook moral injury response. Richard’s not just experiencing PTSD (though he has that too). He’s experiencing moral injury – psychological distress from perpetrating, witnessing, or failing to prevent acts that violate his moral code.

The distinction matters:

PTSD is fear-based. It’s your brain trying to protect you from danger by constantly scanning for threats. Hypervigilance, flashbacks, avoidance – all designed to keep you safe from something that already happened.

Moral injury is guilt and shame-based. It’s not “I might die” – it’s “I did something terrible” or “I was part of something terrible.” The symptoms overlap with PTSD, but the core wound is different. It’s not fear, it’s a violation of your sense of who you are.

Richard shot a child who was charging at him with a knife. Legally justified. Tactically sound. And morally devastating. Because Richard knows that child was produced by a system that Richard is part of. He’s both victim and perpetrator, and there’s no therapy framework for that contradiction.

“Hitting the bottle to soften the blow” – self-medication. Same as Vincent, same as countless people I worked with over 30 years. When professional help isn’t enough, when therapy plateaus, when you’re still functional enough to keep your job but not functional enough to feel human – you drink.

“Friends on the force don’t call, don’t show” – police culture has a huge problem with this. There’s the expectation that you should be tough, that you can handle it, that showing vulnerability is weakness. So when someone struggles, often they’re quietly abandoned. Left to deal with it alone.

No rebound, no yo-yo and so, the time it moves slo-mo, you see the—”

That rapid-fire delivery captures the racing thoughts, the rumination, the mental chaos. Then “slo-mo” and the music literally slows – time distortion. When you’re traumatised, time doesn’t work right. Moments stretch out. Days disappear. You’re simultaneously stuck in the past and unable to be present.

Orphan killed his sister, but his sister was removed when

The mother died in child birth, but dying womb life bring

The cycle of samsara, always was, quite amusing”

This is where Ren reveals the cosmic cruelty of it all. The case can’t be closed because the motive makes no sense. Why would Screech kill Jenny? He didn’t know her. They were strangers. The crime appears random, senseless.

But once you know they’re twins, once you know they were separated at birth, once you know Violet’s story – it’s not random at all. It’s the inevitable collision of two trajectories set in motion 14 years earlier when Violet died giving birth.

“The cycle of samsara, always was, quite amusing” – that bitter irony again. There’s nothing funny about it. It’s the wheel of suffering grinding people up, and Richard is beginning to see the whole mechanism.

The brother never met his sister, didn’t even know

So the tragedy was a catastrophe, a fate fucked up

Richard’s losing sleep, while his whole family’s tucked up”

Richard can’t tell anyone the full horror of what he’s processing. His family’s tucked up safe in bed. They don’t know what he knows. They don’t carry what he carries.

This is the isolation of trauma. You can be surrounded by people and completely alone with what you’ve experienced.

Part 3: “The Five Stages of Grief” – The Therapy That Can’t Fix It

Richard in therapy, processing grief through the clinical model

Now we’re in Richard’s house – it looks like a counselling session happening at home. The music shifts again – more methodical, almost clinical. Ren walks us through the five stages of grief model as Richard experiences them.

For loss comes with a cost like frostbite

Shockingly cold, paving the road to decomposure, decomposing your soul”

That opening sets up the clinical framework, but also warns us: this isn’t neat. “Decomposing your soul” – grief doesn’t just hurt, it breaks you down at a fundamental level.

Stage 1: Denial

Pretending for a while, reality retired, but everything is changin’, Richard lost the will to smile

How to reconcile when murdering a child?”

Denial isn’t “I don’t believe this happened.” It’s “I can’t integrate this into my understanding of reality.” Richard killed a child. That fact exists, but accepting it means accepting that he’s the kind of person who kills children. So reality gets put on hold while his brain tries to sort that out.

“Lost the will to smile” – anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure. Not just sadness, but the absence of positive emotion entirely.

Stage 2: Anger

Anger damned the man that served the hand, that wrote the plan

If God is will, there’s good and grand, they’re dumb, we are, we all are damned

Forsaken by creation, revelations Richard can not stand”

Richard’s anger isn’t at Screech, it’s at the system. “The man that served the hand that wrote the plan” – the politicians, the economic structures, God, fate, whatever force designed a world where 14-year-olds charge at cops with knives and die on the street.

“We all are damned, forsaken by creation” – Richard’s having a crisis of faith. If there’s a benevolent creator, how does this happen? If there’s justice, where is it?

Stage 3: Bargaining

‘Lord, I know it is a reach, but I’m begging on my knees

Resurrect the boy James, resurrect the boy Screech

I’ll devote my life to thee, I will live a life of peace'”

This is the magical thinking stage. Richard knows intellectually that Screech can’t come back, but emotionally he’s negotiating. “If you bring him back, I’ll be good, I’ll change, I’ll devote my life to peace.”

Notice he uses both names – James and Screech. The legal name and the street name. Richard’s seeing the full person – not just “the suspect,” but a 14-year-old boy who had a life and a nickname and people who cared about him.

Stage 4: Depression

Depression, demonic light possession

It feeds upon his spark for life, no water is refreshing

No sunlight brings him warmth, no sleep will ever bring restin’

His guilt and doubt are also loud, the silence sounds so deafenin'”

“Demonic possession” – that’s what severe depression feels like. It’s not you anymore. It’s something that’s taken residence in your body and is using your voice to tell you you’re worthless, you’re guilty, you should die.

Clinical markers:

- “No water is refreshing” – nothing provides relief, not even basic needs

- “No sunlight brings him warmth” – complete emotional numbing

- “No sleep will ever bring restin'” – insomnia or non-restorative sleep, hypervigilance continues even in sleep

- “The silence sounds so deafenin'” – intrusive thoughts, rumination, can’t escape your own mind

The negative obsession ruminating in oppression

But the stressing is a lesson when your mind begins reflecting

And that’s stage number five”

“Ruminating in oppression” – clinical rumination, where you can’t stop thinking about the trauma, can’t redirect your thoughts, stuck in a loop of guilt and “what ifs.”

Stage 5: Acceptance

Just stated. Not explored yet. Because Richard hasn’t actually reached it. He’s gone through the stages in therapy, but acceptance is coming next – and it’s not what you’d expect.

A word about the five stages of grief model: As a mental health professional, I need to be honest about this. The five stages model (developed by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross) is useful as a framework, but it’s not gospel.

People don’t move through grief in neat, linear stages. You can stay stuck in anger for years. Depression can come and go in waves. Some people never reach acceptance – and that’s not a failure, that’s reality.

Particularly with moral injury, where the wound isn’t just loss but guilt and complicity in harm, “acceptance” might not even be the right goal. How do you accept that you killed a child, even if it was justified? How do you accept that you’re part of a system that produces these tragedies?

Richard reaching “acceptance” in therapy doesn’t mean he’s healed. It means he’s learned to function again. But functioning isn’t the same as peace. And as we’re about to see, acceptance of the trauma doesn’t mean acceptance of the system that caused it.

Part 4: “Acceptance” – The Uplifting Lie

Richard preparing for his first day back – hope and healing before reality crashes back in

The music completely transforms. Uplifting piano. Singing instead of rapping. This is the therapy success story. This is Richard healed, ready to go back to work.

The road’s never quite ideal

The slow rise, dust it off

And let me tell you something, Richie, man, I’m proud”

The narrator (Ren) is being Richard’s cheerleader, his therapy voice, his support system. “I’m proud” – validation, recognition of the work Richard’s done.

It felt like a regression but that flesh was set for healin’

You wrestled imperfections, misdirections, walked with demons

Most demons are a fallen angel, truth has double meanings”

This is the language of therapy and recovery. “Pulled a stitch from the seam” – you had to open the wound to clean it properly. “Walked with demons” – confronted your trauma. “Truth has double meanings” – cognitive reframing, finding new perspectives on what happened.

It’s all clinically sound. This is good therapy work. Richard has processed his trauma, integrated the experience, found meaning in the suffering.

The biggest curse you’ll ever face could be your greatest blessing

Remember in the darkest times, no need for second guessing

No path is ever linear, a stumble leads to stepping”

“Trauma turns to lessons” – post-traumatic growth, the idea that suffering can lead to positive change. “The biggest curse could be your greatest blessing” – classic reframing.

And look, this isn’t wrong. These techniques work. Cognitive behavioural therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, trauma-focused therapy – they genuinely help people function after trauma.

But here’s what’s missing: none of this changes the system that created the trauma.

When it gets colder, whatever, it’s only weather

Rain feeds the crops, let ’em grow, think clever”

Resilience language. Growth mindset. “Rain feeds the crops” – even suffering has purpose. These are the mantras that help people survive.

I know you’re itchy, my boy, to get to work and deploy

Serve and protect, my don, and for the right reason

I know you think you’ve done wrong, but look at who you’ve become”

And there it is: “serve and protect, for the right reason.” Richard’s going back to work. He’s processed his trauma. He understands what happened. He’s going back to serve and protect, but this time with awareness, with compassion, with intention.

This is the redemption narrative. The hero wounded but wiser, returning to the fight with new purpose.

Hold that head up high, my friend, come on!

We’re all proud of you, Richie

I hope you get out there and smash it, I mean, what could go wrong?”

“What could go wrong?”

Everything.

Part 5: The First Day Back – Reality Crashes In

And the music cuts. No more uplifting piano. We’re back to hard hip-hop. Richard’s first day back at work.

He encounters Vincent – bruised, battered, on his knees with a guitar. Just got into a fight in an alleyway, heard the cops coming, smashed a bottle, stabbed someone. Another casualty. Another Screech. Another product of the system.

Was his first day back at work after a time of absent leave

Working London on the night shift, what he didn’t think he’d see

Was a boy with a guitar, bruised and battered on his knees”

“What he didn’t think he’d see” – Richard thought he was healed. He thought he’d processed it. He thought going back to work would be different now that he understood.

But the system hasn’t changed. The cycle hasn’t broken. Here’s another Vincent, another Screech, another Jenny – another person the system locked up before they ever saw a cell.

Not so quick to find a trigger, ‘Not so fast’

But Richard was a righteous man who lived inside the law

So he leapt upon poor Vincent and he cuffed him to the floor”

This is the devastating irony of the entire tale.

Richard HAS changed. He’s cautious now. He doesn’t shoot Vincent like he shot Screech. He’s learned. The therapy worked.

But he’s still “a righteous man who lived inside the law.” He still has to arrest Vincent. He still has to be the instrument of the system he now sees clearly as unjust.

All that healing, all that therapy, all that acceptance – and his first day back, he’s doing the exact same job he was doing before. Arresting another victim of poverty and trauma. Locking up another person who was already locked up.

The cycle continues. Richard is locked in his role. Vincent is locked in a cell. The system keeps producing casualties, and the people who process them – police, nurses, social workers, all of us working within the machinery – can achieve all the personal healing we want, but we’re still turning the wheel.

What This Means: Moral Injury and the Impossible Job

Richard’s Tale is about a specific kind of trauma that we don’t talk about enough: moral injury in systems work.

I spent 30 years as a mental health nurse. I’ve experienced versions of what Richard’s going through. You see the system failing people. You see the same patients cycling through crisis, admission, discharge, crisis again. You see poverty, trauma, and neglect producing predictable outcomes. You see people who need housing, safety, and support getting medication and a crisis phone number instead.

And you’re part of it. Not because you’re evil, but because you’re working within a structure that isn’t designed to heal – it’s designed to manage. To contain. To process people through and back out again.

Moral injury occurs when:

- You perpetrate, witness, or fail to prevent actions that violate your moral code

- You’re operating within a system whose values conflict with your own

- You achieve class consciousness while working for the class enemy

- You understand the structural causes of suffering but your role requires you to treat symptoms

It’s the cop who understands that policing poverty isn’t justice. It’s the nurse who knows the patient will be back because they’re being discharged to the same conditions that made them sick. It’s the teacher who sees gifted kids falling through the cracks because funding follows postcodes.

You’re not traumatised by danger – you’re traumatised by complicity.

Richard’s acceptance of his trauma is real. But it doesn’t change his job. He can’t refuse to arrest people. He can’t change the laws. He can’t fix the system that produces Vincents and Screeches.

So what does he do? He goes back to work. He’s cautious now. He doesn’t shoot. But he still arrests. Still processes. Still turns the wheel.

This is what makes Richard’s Tale so brutal: it shows us that individual healing can’t fix systemic rot. Therapy helps you cope with your role in the machinery, but it doesn’t stop the machinery.

The Musical Journey: From Trauma to False Hope to Reality

Ren’s musical choices mirror Richard’s psychological journey:

Part 1: “Locked Up” (90s boom bap)

Hard, driving, systematic. The sound of policing, of the van ride, of Richard processing what he’s seeing. The beat is relentless – like the system itself.

Part 2: “Set The Scene” (hip-hop with double-time sections)

Frantic, chaotic, disorienting. Richard’s mental state in the aftermath. The double-time rap captures racing thoughts, then “slo-mo” and the music literally slows – time distortion, dissociation, trauma’s effect on perception.

Part 3: “The Five Stages of Grief” (methodical, clinical)

The most structured section musically. We’re in therapy now, walking through a clinical model. The music reflects that – measured, analytical, descending through the stages with almost academic precision.

Part 4: “Acceptance” (uplifting piano, singing)

The complete tonal shift. This is hope. This is healing. This is the therapy success story. Ren’s singing, not rapping – vulnerability, emotion, the relief of reaching acceptance. The piano is warm, supportive, encouraging.

It’s beautiful. It’s genuine. And it’s not enough.

Part 5: Vincent’s arrest (back to hard hip-hop)

Reality crashes back in. The hope was real, but the system hasn’t changed. The music returns to the hard beat because Richard’s back in the machinery, and the machinery doesn’t care that he’s processed his trauma.

That musical arc – from trauma to chaos to clinical analysis to hope to crushing reality – is the journey of everyone who tries to do good work within unjust systems.

Why This Matters: The Tales as Mirror

Vincent’s Tale shows us the victims – people locked up by circumstances before they ever committed crimes.

Richard’s Tale shows us the enforcers – people who understand the system’s injustice but whose job is to enforce it anyway.

Both are trapped. Both are casualties. The system grinds them both.

Richard isn’t the villain of this story. He’s not the “bad cop” who needs to be replaced with a “good cop.” He IS a good cop – that’s the tragedy. He’s compassionate, thoughtful, self-aware, traumatised by violence, cautious with his use of force.

And it doesn’t matter. Because his job isn’t to fix the conditions that create Vincents and Screeches. His job is to arrest them after they break.

This is Ren showing us that there’s no individual solution to structural problems. Richard can heal his trauma, but he can’t heal the system. Vincent can reach acceptance in his cell, but it won’t change the poverty and neglect that locked him up in the first place.

The cycle of samsara keeps turning. The wheel of suffering grinds on. And everyone – victim, enforcer, witness – is caught in it.

What Comes Next: Vincent’s Tale – Starry Night

Tomorrow evening, Ren drops Vincent’s Tale – Starry Night. Another Van Gogh painting, another chapter in Vincent’s story.

Starry Night is one of Van Gogh’s most famous works – painted in 1889 while he was in the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum. It’s a view from his window, the night sky swirling with energy and chaos, the village below peaceful and sleeping.

What does that mean for Vincent? Is this Vincent in his cell, looking out at a world he can’t access? Is this the chaos in his mind versus the calm he can’t reach? Is this hope, or is it madness?

We’ll find out soon. But knowing Ren, it won’t be gentle. Vincent’s locked up – literally now, metaphorically always. And the bedroom was just the beginning.

Join The Vault Community

Enjoyed this breakdown? I’m building a space for RENegades to dive deeper into the lyrics and stories. Join 200+ fans on Facebook.

Follow on FacebookFuel the Next Deep-Dive

I keep this site ad-free and independent so I can stay honest to the art. If you found value in this, tips are never expected but always appreciated.

Renflections

What hit you hardest about Richard’s Tale? The therapy arc? The first day back? The realisation that healing yourself doesn’t heal the system?

Drop your thoughts below. Let’s talk about moral injury, impossible jobs, and what it means to be locked up in a role you can’t escape.

The Vault of Ren is a fan-curated project celebrating the art and storytelling of Ren Gill, with clinical perspectives from a former mental health nurse with 30 years’ experience. All analysis represents personal interpretation informed by professional knowledge, not official statement from the artist.